The phrase “merciless Indian savages”, penned by Thomas Jefferson in the U.S. Declaration of Independence, is one of the most widely recognized examples of how the United States government has described Indigenous peoples. Yet it is only one of countless dehumanizing terms that have appeared in federal records, laws, policies, reports, and correspondence over the course of U.S. history.

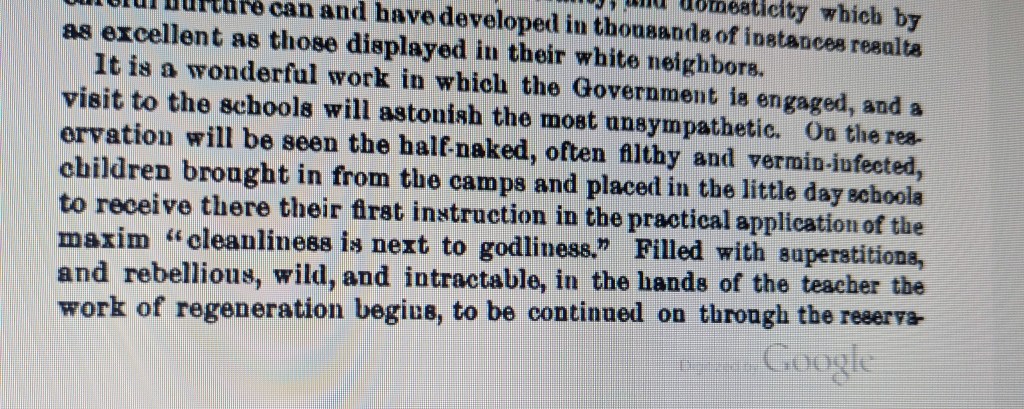

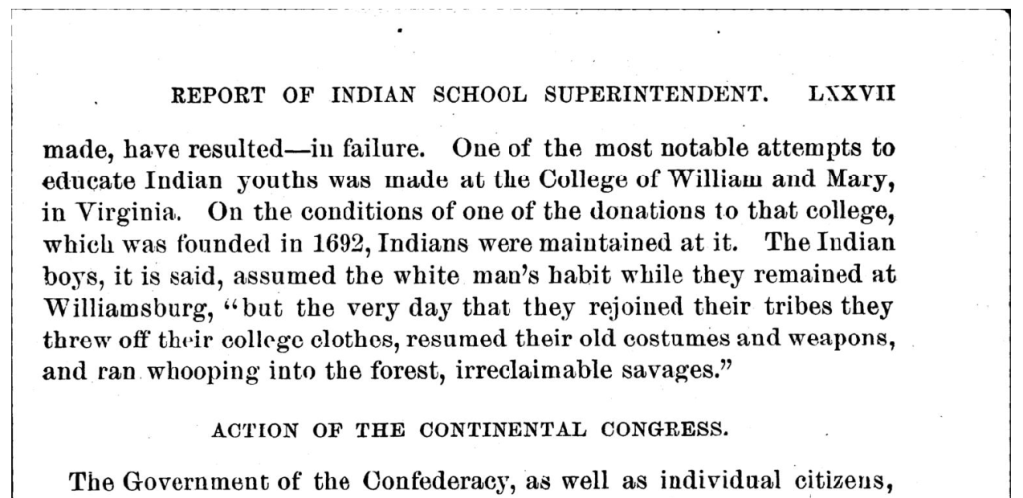

Irreclaimable Savages is a project that documents these descriptors exactly as they appear in official government sources. Each entry will cite its original context to make visible the language that has shaped public policy, justified violence, and reinforced systems of removal, assimilation, and erasure.

This is not a project about shock value. It is a project about evidence.

Many continue to say, “This is not who we are.” But when we examine the archival record, phrase after phrase, document after document, it becomes undeniable that dehumanizing language has been a consistent and institutionalized feature of U.S. governance. The purpose of this site is to make that record accessible, searchable, and impossible to ignore.

Dehumanization is not harmless rhetoric. When people are described as less than human, it becomes easier to justify their dispossession, their displacement, and their death. Language is not separate from policy; it prepares the ground for it. Naming that truth is the first step toward refusing its continuation.

The title “Irreclaimable Savages” is taken from a term I encountered while researching Federal Indian Boarding School archives. It was one of many phrases applied to my ancestors, phrases buried in thousands of pages of official documentation, but still echoed today in subtler, normalized forms.

I am a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. I am a PhD scholar, a researcher, a parent, a daughter, an aunt, a neighbor, a friend, and a stranger. Above all, I am a concerned citizen committed to public truth-telling. This work is meant to be shared, cited, taught, questioned, and expanded. The archive is not neutral, so neither is this project.

May this site help us remember, and may remembering move us toward accountability, care, and collective repair.